The Idea that was Automation and Disproving Early Misconceptions

November 7, 2017

By: Owen Hurst

Recently, while doing research, I came across an interesting article that forced me to stop and consider how insightful the article was when we consider the current application of automation on the manufacturing industry. The article titled “The Scope of Automation” by S. Moos was originally published in the Economic Journal in 1957.

In the article Moos defends the growth of automation against a rising tide of negative opinion and narrow-minded consideration of its applications. Now it is important to note that this is 1957, and the idea of automation was not the same as we think of it today. Moos identifies this and the difficulty with fully defining automation, but his primary focus throughout the article is on the implications it will have on manufacturing, which fits rather well with our current understanding of the term. For Moos, “automation is the combination of the various modern techniques which yields a “breakthrough” in production methods.”[1]

As mentioned above his intent was to defend automation, and he identifies three common misconceptions he wishes to disprove:

- 1) The scope of automation is limited to a small range of industries, firms and products.

- 2) Automation will not bring any fundamental change in industrial organisation, as it represents only a continuation of mechanisation, rationalisation and scientific management as practiced during the last fifty years, Automation will advance at the ordinary rate of technical process.

- 3) Automation will lead to a higher degree centralisation and strengthen monopolistic tendencies.

Considering what we know of automation today Moos was quite insightful in his pursuit to disprove the above “predictions” regarding automation. He identifies that even in his day automation was changing things, “industry of today has at its disposal mechanisms which can count remember, measure, compare, inspect, test, correct, start, stop, slow down and accelerate production.”[2]

To provide a full response to the above concerns Moos has broken his argument into several sections that include: Which size of firm will be most affected, effect on location of industry, long runs vs. short runs, industries most affected and the electronic computer. He also considers Office automation, which has been left out of this discussion.

When considering the size of firms that will be most affected Moos was quite right to identify that automation was going to change small businesses just as much as larger firms and that automation would allow small firms to compete with larger ones. He noted that automation may “reduce size as measured by number of employees yet increase size as measured by capitol used or by turnover.”[3] On the whole his finding regarding the size of firms is that “automation is likely to reduce size-determined differences in efficiency of work, quality of output, overheads, and therefore manufacturing cost per unit.”[4] Moos’ theories on the future of automation in 1957 were accurate and well ahead of the technology that would fully embrace his vision of automation.

Moos was not alone in his predictions, although they were not wholly embraced either. He was supported in his perception by D. S. Parker, VP of the US Ford Motor Co., at the time who stated of automation that “the idea that only the very large, mass-producing industry could successfully use it, has been disproved again and again . . . automation is a new concept of manufacture . . . instead of smaller plants going out of business, they will use more automation.”[5]

However, he does insightfully note that certain sectors, such as ‘flow-industries’ that deal in fluids like the oil and chemical industry are better suited to large firms and as we know he was primarily correct on that account as well. One interesting point was that Moos included breweries within the ‘flow-industry’ and although brewing remains dominated by large firms the rise of micro-breweries has increased substantially in recent years, particularly those utilizing control and automation systems.

Moos’ theories regarding location are also quite intriguing. He notes that the increased use of automation and decrease in labour force, with factories able to operate with a labour force of hundreds rather than thousands will likely decentralise. Firms will no longer need to stay close to major cities but will expand into smaller towns. His theory proved correct in the short term, however it fell short of the long-term development of metropolitan centres, which have seen a steady rise in workforce, while many small town are now seeing the reverse effect of what Moos predicted.

Long runs and short runs played a significant role in the rise of automation, long runs being the mass production of a single item, and short runs being small scale production of an item. Moos has a unique way of identifying the incorrect ideas by others in this area, he states that “according to the mythology of automation, not only large-scale enterprise and centralised production but also “long runs” are required for automation to spread.”[6] He argues that this idea has no evidence or validity, but that new developments in automation allow for faster production and for faster adjustment between runs.

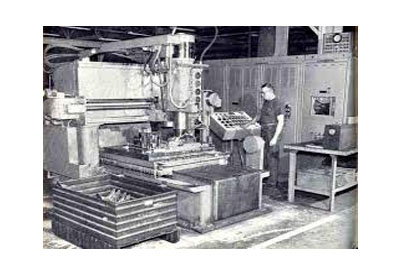

In 1957 the new developments were made possible by the tape control of machine tools. Much in the way software sends the signals to the machines a tape card was the revolutionary data component of the time. Moos said that “the working of the tape requires a ‘methods engineer,’ a ‘programmer’ for developing the instructions, a clerk for punching the instruction card and an unskilled operator – who replaces highly skilled machine-tool personnel – inserting the tape.”[7] The use of tape control was a clear precursor to modern automation and allowed Moos to make the prediction that “the introduction of automation, together with firms’ desire to reduce costs per unit to a minimum, will speed up the much-needed progress in the standardization and simplification of products which has been advocated so often for the purpose of cost reduction.”[8] He saw very early the trend to standardization and simplification that control components are striving to fully achieve today.

When considering what industries would be affected by automation Moos wise was not to be definitive in the sectors that would be most effected. He noted that the manufacturing industry would bear the brunt of the automation wave, but other industries and fields would also be affected. However, Moos had the foresight to note that “one has to bear in mind that different industries will introduce automation at different times and in different degrees according to technological developments and to economic conditions.” Moos was able to look beyond the technology of his time and recognize that advancements would carry automation beyond the current scope of understanding in 1957.

And finally he considered the applications of the electric computer. The computer had Moos thinking revolution, even if he identified the electronic computer as being the second industrial revolution, a point which we have today reconsidered with our current focus on Industry 4.0. But nonetheless he saw its implications for automation in the manufacturing sector. At the time computers were primarily engaged in use as computing machines in the office, and thus Moos’ early discussion of office automation. Although in 1957 many yet saw the full implications for use in automation and control he noted that computers were ideally suited for this field because “the revolutionary significance of the electronic computer lies in its speed, its precision, its reliable memory for a selected field of facts and its capacity for long, uninterrupted work.”[9]

He believed that the electronic computer had a wide range of capabilities for production, distribution, administration and research, and his beliefs have proved true.

In his conclusions he identifies that the growth of automation will depend not only on technological advancement but also on the attitudes of the government and of industrial and labour leaders. But regardless “automation will spread, and so will its influence on the future structure of industrial organisation: size and location of firms, the growth of new industries, employment and investment, rate of technical progress, the division of labour, the distribution of income, wage differential and working conditions, managerial functions, time and motion study, cost accounting, especially with regard to overheads.”[10]

Today, we live with the automation Moos dreamed about 60 years ago.

Image source: https://hackaday.com/2016/11/11/an-introduction-to-cnc-machine-control/

Source:

Moos, S. “The Scope of Automation,” in The Economic Journal 67 (265)(1957), pp. 26-39

[1] Moos, The Scope of Automation, p.1

[2] Moos, p. 26

[3] Ibid, p. 27

[4] Ibid, p.28

[5] Ibid, p. 28

[6] Ibid, p.31

[7] Ibid, p.31

[8] Ibid, pp.31-32

[9] Ibid, p.35

[10] Ibid, p.39

Owen Hurst is Managing Editor of Panel Builder & Systems Integrator