The Rise of System Integration

November 21, 2017

BY: Owen Hurst

System Integration has a strong foothold and is a key driver of advanced technology that is increasingly focused on cost saving coupled with higher production rates. However, the evolution of system integration was slow, and does not necessarily meet the exact standards we think of today when we hear the term or consider the type of work system integrators do.

To fully understand we need peer back in time to some of the early inventions that may not have focused on the use of fully connecting electrical sub systems, but certainly developed the rudimentary begins of a field that has increasingly important applications today. We can look back to the work of Thomas Edison in the early 1880’s. When most hear Edison’s name it is the incandescent light bulb that comes to mind, but to make the bulb work and to be able to market it Edison also had to develop a power distribution system. Currently there were distribution networks in place for gas, and it was looking at this that gave Edison the idea to distribute electricity in an analogous manner. However, Edison had to conceptualize the entire systems and develop the components to make it work. Although very rudimentary it was the development of the power distribution system by Edison that got the idea of electrical system integration underway.

Building directly on the work of Edison was George Westinghouse who began to study the DC system that Edison had advanced. He soon came to the conclusion that an AC based system was more promising and provided better control. And thus only a few years after Edison Westinghouse instituted an AC power system for electrical transmission. One notable difference from Edison was the intended goal. Edison had been focused on bringing electricity for lighting to people’s homes. Westinghouse was much more focused on the industrial sector and the advantages power distribution would bring to manufacturing. In the end both systems would prevail and find niche markets.

Thus far advances had come primarily from inventors such as Edison and Westinghouse, although we must note that other inventors had also worked and made advances here, Edison and Westinghouse are simply the primary drivers and most notable. But as industry advance demand for greater use of technology and systems gave rise to corporate R&D divisions. These divisions would greatly impact the market and kickstart the rapid advancements in new tech that R&D departments have maintained to this day. The list of names and companies that made advances through R&D divisions are too great to name here, but suffice it say systems began to evolve and move beyond power distribution and into the wider sectors we recognize as system integration today. By the early 1950’s the advantages of complex integration and the effectiveness of integrating independent subsystems into a cohesive automation system were at the forefront. However, these advances would meet with skepticism and a degree of fear as integrated systems and automation began to make unskilled labor positions obsolete and were beyond the understanding of many people, who chose to scoff at what they could not understand.

If we were to look back at the earlier stages of automation there was considerable hesitancy in regard to automation and its effectiveness for manufacturing. An article by S. Moos published in The Economic Journal in 1957 entitled “The Scope of Automation” identified the general public concerns with automation. Moos identified that in 1957 individuals believed that the scope of automation was “limited to a small range of industries, firms and products” and that “automation will lead to a higher degree of centralization and strengthen monopolistic tendencies.” He attempted in his work to explain the term automation and identify how automation will affect industry positively. An effort he hoped would dispel much of the hesitancy and fear regarding the advances being made.

Moos’ predictions were insightful in a number of ways, he identified that “automation may reduce size as measured by number of employees yet increase size as measured by capitol used or by turnover.” His research further identified that in 1957 automation was being utilized to “count, remember, measure, compare, inspect, test, correct, start, stop, slow down and accelerate production.”

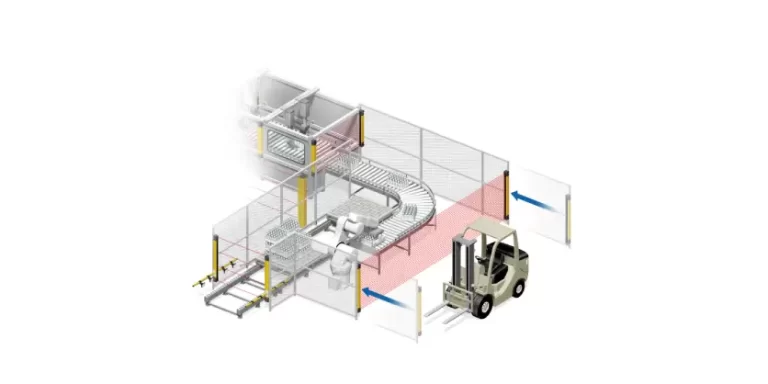

Today we broadly automate within the same classifications identified in 1957, however we have expanded our ability to link each of the identified uses into one system, a progression that necessitates expansion of system integration firms and existing companies advancing their business model to include system integrators or control divisions.

The focused position of system integrator and designated system integration firms gained a solid foothold in the late 1980’s and into the 1990’s as technology made significant advancements and control technology became increasingly complex and open. Integrators have developed a dynamic relationship with end-users, both serving the market as independent firms as well as increasingly their employment with end-users who require continued system advancement and monitoring in-house.

Their relationship with suppliers is likewise dynamic in that they are naturally customers but in terms of certain suppliers can also be direct competitors. In terms of product sales integrators are an important part of the sales channel, and companies developing products are increasingly focused on targeting system integrators to expand the market. At the same time, it has been identified that in the case of large-scale project bids OEM engineering firms at times compete with system integrators where there is potential for significant product revenue.

Thus, for today’s electrical and engineering firm’s system integrators can represent an important part of a company’s revenue stream and provide further savings through experienced product selection and project design. If we consider the global forecast of business and government spending on consulting and system integration work in just a few short years global expenditures have risen from $232.8 billion (US) in 2013 to $393.5 billion in 2017. (Statista 2017) Further we regularly witness the acquiring of integration firms by large companies focused on securing the local channels that have been developed by small to medium sized integration firms or company divisions.

Sources:

Moos, S. “The Scope of Automation,” in The Economic Journal 67 (265)(1957), pp. 26-39

The Business of Systems Integration, Edited by Andrea Prencipe, Andrew Davies, and Mike Hobday. Oxford Universtiy Press, 20015